Rewriting The Rules of Aging

Guest

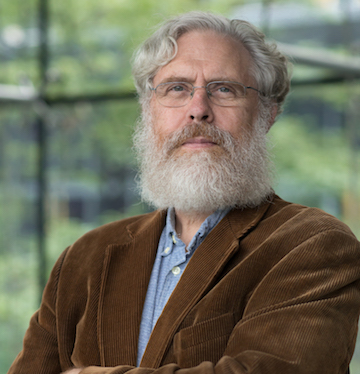

George M. Church, PhD

Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School and Professor of Health Sciences and Technology at Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

George Church is Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School and Professor of Health Sciences and Technology at Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He is Director of the U.S. Department of Energy Technology Center and Director of the National Institutes of Health Center of Excellence in Genomic Science. He has received numerous awards including the 2011 Bower Award and Prize for Achievement in Science from the Franklin Institute and election to the National Academy of Sciences and Engineering.

TRANSCRIPT

Brianna Stubbs:

This episode is presented by Ashton Thomas Private Wealth, guiding families and institutions with clarity today and strength that endures for generations.

George Church:

Evolution is not always doing what we want. It’s optimizing some reproductive function that’s sometimes a little bit obscure in the way that we think about it today. There’s no law of physics that says you can’t live longer than a bowhead whale. It’s all negotiable, we think. We’ll see.

Eric Verdin:

Aging is evolving. No longer are we subject to forces beyond our understanding and control. We have charted the landscape and explored the frontiers of aging.

Brianna Stubbs:

What was science fiction is close to becoming reality, restoring sight, repairing tissues, reviving cells, organs, and maybe even our minds.

Read more close

I’m Eric Verdin, CEO of the Buck Institute.

Brianna Stubbs:

And I’m Brianna Stubbs, a scientist here at The Buck.

Eric Verdin:

On this podcast, we dive deep into geroscience, studying the intersection of aging and disease with some of the brightest scientific stars on the planet.

Brianna Stubbs:

Join us because we’re not getting any younger yet.

Eric Verdin:

Hi Brianna.

Brianna Stubbs:

How’s it going, Eric?

Eric Verdin:

It’s going well. I just sat down with uh George Church.

Brianna Stubbs:

George Church?

Eric Verdin:

Yeah. The George Church.

Brianna Stubbs:

Gosh, he’s a giant in the aging field. It’s impossible to be in this field and not heard of George Church. Trevor Burrus, Jr.

Eric Verdin:

He is, and he’s one of the most provocative thinkers and doers in the field. Well, he he his science is always big ideas, like when he’s proposing to resurrect the woolly mammoth already.

Brianna Stubbs:

That’s one of his problems.

Eric Verdin:

So yeah, and and he has the same ambition in terms of aging science. He wants to really stop aging, and he’s going through a track which is m very few people are going to, which is gene therapy.

Brianna Stubbs:

Trevor Burrus Kind of a lot of uh people would have a bit of like the heap jeebies with the gene therapy. It’s definitely a controversial space, not easy to not easy to be a pioneer, and you have to think a certain way, be a certain type of person to just sort of yeah, like not care what other people think if you’re gonna go hard into that space. Trevor Burrus, Jr.

Eric Verdin:

And that sort of uh epitomizes him. He doesn’t care what other people think in terms of, you know, should we do this, should we not? He’s going to do it first in animal models and then hopefully next in humans.

Brianna Stubbs:

Wow. Well, I’ll look forward to hearing your conversation. It sounds like it’s set to be a fantastic one.

Eric Verdin:

Aaron Ross Powell It’s an amazing conversation. Check it out. Um delighted today to welcome George Church to our podcast. We’re not getting any younger yet. Uh but with uh people like uh George on board in the field, I think it it is only a matter of time. So uh welcome, George. Delighted to have you here.

George Church:

I’m delighted to be with you today.

Eric Verdin:

Your career has been truly expansive and actually has affected many of the people in our audience and in the world in ways that they might not even suspect. So just to give it a little bit of background, when I started sequencing, uh 40 years ago, it would take us three days to analyze 400 base pairs. Uh today, you know, we can sequence uh 3 billion base pairs in in a few hours. And the first human genome cost $3 billion to sequence. Today we can do it for about $150. And in many ways, next gen sequencing was the basis for many of these discoveries. But it’s not only, you know, in terms of human genome sequencing, now next gen sequencing is part of many of the experiments that we do at all levels. So really amazing contribution, and and to have you in a field of aging research uh really is is exciting. So, how did you get interested in aging?

George Church:

Yes, well, I mean I think all of us have have had a cherished family member die of of old age. It’s gonna kill 90% of us, at least in the in the industrialized nations. And uh but the real uh turning point was when uh postdoctoral fellow came to my lab, Pedro Demogales, who is is still a mover and shaker in the uh aging field, he he uh and I embarked on some studies of zoological components, you know, comparing different body masses and and uh longevities and of various animals, uh including extreme outliers. When you you basically plot uh, and these would be uh extremely long-lived relative to their their cousins, other closely related animals. And these are the bowhead whale and the capucha monkey and and uh and naked mole rats. And and we started a couple of databases, which are still, I think, some of the main databases that are used for human and animal aging and age-related genes. And we use those genes very soon thereafter to test out uh dozens of genes, about 48 genes at once in gene therapy. So that was that was my start.

Eric Verdin:

Yeah, so that’s actually really interesting because one of those papers on on the bowhead whale uh discussed something that is not really um discussed much in the literature. It should be a lot more discussed. It’s the whole idea of uh of scaling of aging as a function of body mass. How does body mass translate into shorter or longer lifespan?

George Church:

There’s a correlation uh that as you go up in body mass you get uh long longer-lived animals. Um and in fact, uh many of the of the large body mass long-lived animals have extraordinarily low cancer rates, which is kind of contrary to what you would expect, because cancer is a disease that happens as you replicate your cells. Uh, the more times you replicate, the bigger your body, but also the more errors that you could have. And all it takes is one or two errors to start a process of cancer formation. So it’s very unusual that things like uh whales and elephants have such low cancer, while things like mice, which is really tiny, have high. Um, and then as you have this nice plot of where you go up with with uh body mass and uh uh longevity, there are a few outliers that are even more on long-lived than you would expect from their body mass, and those are the ones I listed uh are were good examples of that. Humans are actually a little bit above the line as well, meaning uh a little bit longer lived than you would expect. Yeah, so I think that’s that’s what you are looking for.

Eric Verdin:

This is one that is still not fully understood, but uh and underlies the whole field of longevity. And um uh, you know, the concept of longevity quotient is also, you know, how does your lifespan correspond to what your body mass is? And it turns out that humans are in some way uh doing extremely well already. That is for for our body mass, we’re living longer than we would expect. Um and mice do exactly the opposite. And it’s been, for me, it’s been one of the arguments why it might not be so easy as as we hope to actually increase lifespan dramatically in humans, because in some way I’ve argued that maybe we are already evolutionary optimized by by virtue of being predators and apex predators.

George Church:

Well, I I I don’t doubt that we are uh somewhat optimized. And the the reason we were studying these long-lived animals uh is that there might be multiple ways that they use to do this optimization, and if you combine them, uh you might go beyond. Uh I mean evolution is not always doing what we want. It’s it’s optimizing some reproductive function that’s sometimes a little bit uh obscure or uh or or frugal in in kind of a pennywise, pound foolish way in the way that we think about it today. Because today we have no shortage of food. Uh uh so we have no sh, in a certain sense, no shortage of body energy to repair, to, you know, to do like double checking of processes to make sure everything’s going okay. Then that was too expensive for our ancestors in a you know kind of a metaphoric evolutionary sense. Um, but now we have a new set of priorities. So I think uh what we’re really doing is collecting a set of genes, proteins that are encoded by those genes, and seeing uh you know what combination of them uh can push things out. There’s no law of physics that says you can’t live longer than a bowhead whale. It’s all negotiable, we think. We’ll see.

Eric Verdin:

George, there are two sort of broad schools, and and they’re not necessarily exclusive of one another in the aging field. One that is focused on repairing the damage that has been done, uh, in some way the replacement school. Um, and the other school is that we should actually prevent the damage from occurring. Uh what do you see is is more important and how do we tackle both of those uh directions in the field?

George Church:

Damage can include damage to DNA and proteins and uh so-called epigenetics, which is how the DNA proteins associate with one another and are produced. Um Yes, I I think our uh ancestors uh were very frugal. We could spend more energy on uh increasing our you know our rate of repair and so forth. It’s actually quite good, but we can make it better. We could put in redundancy. This has been done in uh in animals. You can put in redundant copies of genes that that once they get damaged, they they lead to uh cancer. Now that we have ability to make uh a variety of cell types from stem cells from the patient or possibly generic stem cells, these are distinguished from most of the stem cell therapies in the world which have not been properly vetted, have not been through FDA approval and so forth. But future stem cell projects or where we can make uh the precursors to various cells and do replacement, um, that might end up being better than just trying. I think we can do both. We can we can uh increase the repair processes preemptively and we get uh via better enzymes inside of the cells, um, but we can also replace the cells. Um even in the brain, uh even though the brain doesn’t do a lot of that, uh it can be coaxed into doing more than it than it normally does. So I think these are these are both very promising pathways. Um and it’s not quite clear that the the the the ones I’ve described, whether which path are they working. We are working on one other thing that that didn’t mention that that is appropriate here in terms of making tissues and and organ replacements. Uh we we are making uh organs both based on human cells and based on uh um reprogramming pigs. The pigs are much further along. In fact, we have someone who still has a very active pig kidney after now four going on five months. Uh I met with him the other day and he’s he’s just having a great time uh relative to kidney dialysis. So, but this could be much more general than fixing really broken organs. This could be something where it’s done preventatively um or curatively body-wide.

Eric Verdin:

Truly exciting. And uh the whole idea of uh reprogramming for aging has been has taken the field by storm. And I just just want to spend a little more time on this for uh those members of our audience who haven’t heard about this. So maybe let let’s step back to uh uh Shinya Yamanaka uh uh discovered these four factors that by themselves are able to take any somatic cell. By somatic we means a cell from the body, uh, and to reprogram them into pluripotent embryonic stem cell, meaning a cell that has the ability to uh eventually to divide forever and to become any specific tissue. And so this created a uh a revolution. Do you want to take us to the next step of what uh uh Ipsisua uh uh Belmonte did in terms of the partial reprogramming and how this led to you know this work?

George Church:

Well, well, before we get to uh Belmonte, uh the observation, which wasn’t really intended to have anything to do with longevity, as far as I know, or at least the early adopters were mainly looking for stem cells for which they could reprogram first, they reprogram it from uh uh uh an adult cell into an embryo-like cell, and then back out to a different adult cell. That was the plan. So you can make tissues like that, you know, to solve diabetes and so forth. It was the goal was to make a new, you know, uh have an infinite supply of your favorite missing tissue. But what you know, but but but the observation was that it basically reverted it from, you know, you could take it from an 80-year-old and with treatment with these four factors, uh, you could get to uh uh essentially an embryonic state. And by partial reprogramming of the Belmonte experiment is you could get you could get something that’s just rejuvenated without being dedifferentiated. And that’s important because um the totally de differentiated front firstly doesn’t do a function anymore. It doesn’t it doesn’t uh do a mature function like producing blood cells or um you know uh skin cells or whatever. It it is it’s pluripotent, meaning it can do almost anything, but it isn’t doing anything at that moment. So that’s too far. Um so partial reprogramming uh look uh was hoped to and was shown to um just just cause rejuvenation without complete dedifferentiation to an embryonic state. So it stays in its mature state. And um but that those experiments were uh n not really done in a in a format that where you could uh you could call it a gene therapy and take it to the FDA, and that’s what that’s what uh we added to it. And and again, so we weren’t going for longevity, we were going for um you know, reversing particular age-related diseases, but we decided to let those animals keep living and just see how far they went, and sure enough, there is a longevity effect as well.

Eric Verdin:

Yeah, and as as as we we we discussed earlier, this has taken the field by storm, and not only the field, but also the public imagination, because these were and these are some of the earliest instances in which we can truly uh talk about rejuvenation, a sort of rewinding the clock back.

George Church:

And this is very clearly uh aging reversal at a cellular level.

Eric Verdin:

We know that the field has embraced this uh in a huge way. About a dozen companies in the Bay Area all targeting uh rejuvenation using the same type of approach. One of the key questions, you know, we can clearly rejuvenate in vitro. Um, we can also partially rejuvenate in vivo in animal model. One of the major barriers to bringing this to the clinic has always been the idea of the vector. How do you, you know, if you’re going to be transducing this into a human, hopefully you would have to do it in most cells or most organs, or at least in a significant proportion. So can you tell us a little bit of where how how how do you see us addressing this barrier to, you know, having the right vectors, for example, go into because you could rejuvenate the whole body minus the brain. This wouldn’t help us. And so the brain still remains a tough place to go in terms of uh you know getting enough cells transduced. What’s your thinking in terms of where’s the field moving in this direction? Do you already think it’s going to be doable to get global reprogramming?

George Church:

Well, there’s there’s there’s two directions that it could go that I think are quite hopeful. Um one is that the first three factors we talked about, which were aimed at the blood, or even the Yamanaka factors, which you at first blush you think those, since those they’re not secreted into the blood. They are kept in the nucleus. They they’re they’re transcription factors, they work on the DNA. And so whatever cell, in order to have an effect on all your tissues, you would think you would have to get it into each of the tissues. Um, in other words, the AAV that you maybe inject into the into uh in into the blood would then have to go through the blood and and cross the endothelial layer, that’s the inside of the blood vessels, into each tissue, and then find its target and do its thing. Gene therapy in general is not uh particularly efficient for any tissue other than the liver. So solution number one is the one is that maybe the Yamino factors can act the same way that our soluble factors. We intentionally focused on soluble factors originally, but we you know felt we had to do the Yamako factors as well, and maybe they work the same way. They rejuvenate the liver, and then the liver produces who knows what, but it goes through the blood, and the blood goes everywhere. And proteins, even though it’s hard to get gene therapies delivered everywhere so far, and that’ll be number two when we get to it, is the proteins uh are much more effectively spread throughout the blood. And many proteins cross the blood-brain barrier and get into the brain, which was your your favorite tissue of a few seconds ago. So, number two, though, is to actually target those uh cells, is to uh and we do uh to not count on the blood carrying a protein to those, but actually having the the virus itself go to every tissue, like the brain. And the brain is not just your favorite tissue, it’s everybody’s favorite tissue, um, because we have an epidemic of cognitive decline, a lot of it caused by Alzheimer’s and related diseases. Um, and you know, if you’re gonna live past 90, you got a very, very high chance, I mean, it’s almost guaranteed that you’re gonna have some cognitive decline. So um, so anyway, so one of my other companies, uh not Rejuvenate Bio, but Dynotherapeutics, um, set this as their as their um uh uh mission was to get AAV that normally, and in fact, most viruses and most non-viral deliveries go to liver. They said, let’s get it away from the liver and towards the brain. And and to do this, there were there were two key tools that that had been used separately with some success, but together they’re amazing. And those two tools are uh artificial intelligence, uh, machine learning, and the other one, the second one is uh large libraries. So use artificial intelligence to make Large libraries of variations on the capsid that is going to be targeting the brain, but normally doesn’t, change the surface so it will recognize various components that lead it to the neurons in the brain. And the AI helps you make sure that you you maximize the bang for the butt for the number of mutants. So we’re going to make about a million mutants. Well, we did make a million mutants. And we want to eliminate those that are clearly deleterious based on AI, and those that are clearly redundant and um you know neutral of no interesting change, and focus on lots of change that isn’t going to kill the capsid. Oh, and then the third trick uh is to inject it into uh an animal, which is the best human model we have. It’s normally avoided because they’re very expensive, which is primate models. You know, baboons and um rhesus monkeys and so forth. Uh and but the reason we could afford it, doing a million uh primates would be unaffordable to almost anybody. Um we could we we did a million at once. So we can inject all these payloads where the DNA encoded a barcode and the capsid was different for each virus, and then we could find the ones we could just take a little bit of brain, a little bit of liver, and say detarget the liver and increase the target of the brain. And we ended af after that process, we ended up with um a hundredfold improvement in delivery to the brain and a tenfold detargeting of the liver. And I and I think this is a general thing. We could probably we are hoping to do this with every tissue that is of significance to age-related diseases. You know, so definitely the brain and the immune system, very important targets for um aging.

Eric Verdin:

I agree. There there’s a recent uh number of papers suggesting that those two organs, you know, brain and and immune system, which are the only sort of distributed organs, actually play a rate-limiting role in in aging. That is, if you have immune aging, you get organismal aging the same with the brain. So I think it’s fascinating. I mean, immune system is much easier to target, but uh it’s amazing to hear that uh using these types of selection techniques you’re able to enrich for uh new AAV vectors that will bring the payload to the brain. It’s fascinating to see. So we are we’re on the verge of revolution. Uh it and in some way the revolution is already ongoing. It started about 20 years ago by uh the work of Gary Rufkin and Cynthia Kenyon and and Tom Johnson and all those showing that aging was actually tractable using the tools of molecular biology, and we know these tools have been incredibly powerful for for any any subject that we’ve tried to tackle. So um where do you see this field going?

George Church:

Yeah, well, I think uh one thing that seems to be happening is uh that clinical trials uh are getting shorter. Um, safer. So it used to be that long trials were necessary to get safety. I think we’re getting safer. Uh, and this includes gene therapy. So the the COVID-19 vaccine was delivered basically as a gene therapy. It was a lipid nanoparticle outside and uh a messenger inside, and there were some of the vaccines that were actually viral outside and double-strand DNA inside. Uh, and and those went through about uh six billion people uh received those, and so they were safe and effective. And that was about uh some of those were uh developed in 11 months, so that was much faster than the normal of 10. And uh we just saw um uh a gene uh therapy delivered developed for a single individual baby. There was a kind of a uh a hurry to do that quickly because the you know the baby had a a unique disease which was not on the list. You know, that’s like the ultimate in the individualized therapy. And that that also went quickly in in months and uh and probably could be repeated for additional diseases. Now I think the the real payoff for gene therapy is for very common diseases because they’re it’s affordable. Uh so it’s uh like $20 uh a dose for for the COVID vaccines, and it probably could be a uh in in that range for uh anything that has a really big market of billions of people, and certainly uh we’re all susceptible to aging and uh and and the consequences of aging are not just death, but you know, ability to do one’s job. So huge economic consequences.

Eric Verdin:

Aaron Powell What you’re saying is that you see within the next 10 to 20 years, gene therapy uh based on these vectors and this technology is going to become much more available and and and allow us to do much more customizable type of treatment. So you that that that’s your vision.

George Church:

Yeah.

Eric Verdin:

What is your whole philosophy about aging in general?

George Church:

Well, I don’t think it’s that fundamentally different from most aging uh researchers are studying aging. Well, maybe it’s a little different in that I I think that we need to take uh a lot of shots on goal, but at a very close to human level. So so I I think it’s not sufficient to get things to work in tissue culture cells. We need at least organoid, human organoids, and uh, and maybe humanized primates uh would be uh be even better because a lot of these are systems problems. They’re they involve their interactions between the immune system starts to fail, and then the and then neuroendocrine and and uh kidney failure and so forth, you start uh you have multiple systems failures, and so you want to you want to see how that works out in a in a in a tank body. So I think we’re gonna start the kind the kind of multiplexing that I was talking about, where you can inject a million different capsids just to see where they would go, is just a start. You can also um not only see where it goes, but the kinetics at which it decays, the how long it lasts, um and whether it solves the problem at least locally, you know, and so you can sample each tissue and see whether the the the drug, the the in this case the gene therapy is being uh effective. And the nice thing about gene therapies, in addition to all the advantages I’ve already mentioned, is they contain barc barcode tags. And so if you can see that it’s doing something good here, uh then you can check out the barcode tag and know which which of the million viruses uh was doing doing the trick. So I think that’s gonna be uh increasingly the case. And and I think moreover, we’re getting to the point where um we can try various combinations. Combination therapy is very common in certain parts of pharmacology, in particular cancer uh, you know, fungal, bacterial, and viral pathogens. In each of these cases, you use three, four, five different drugs that hit different targets, or maybe some of them hit the same target uh to make sure there’s no escape. Um here we’re not using it because we’re worried about escaping so much as there are multiple pathways we have to get simultaneously. Otherwise, it’s like whack-a-mole. We not knock down cancer, but then ten other things will kill you. And so you want to get all 10 at once. And you get close enough to that we might hit uh the point where science is advancing faster than our aging is.

Eric Verdin:

Uh, in humans, correct mutations. I mean, this is what we’re doing first. We’re correcting mutations if a kid is sick. But the same technology in principle could be applied to actually improving our our own lot. And so this brings up a whole series of questions, and I think in many ways, I think humanity is not ready for this. But I would love to hear, as we saw by an attempt that was done in in China, I believe, to make uh children resistant to uh to HIV by knocking off the receptor. Um so what is your your thinking about the ethics of um us in some way taking control of our own destiny via genetic manipulation in the future?

George Church:

Well, first of all, I I I uh I think what you’re talking about is not taking control of our destiny, it’s taking control of the destiny of our descendants. And I would say my critique of uh you know what’s been done so far and what we’ve been considering is that um uh there there are two big problems. One is that let’s say you want to solve one of the major health threats today, which is cognitive decline. Typically a slate onset after you know after age 80 or 90. Um and so the clinical trial for that um would if you wanted to do it through the germline, through babies, uh, would be 80 years. And if you f if it fails, then it’s another 80 years. So we’re talking about century and a half from now, and that’s just that’s just not uh feasible with current economics and health economics. The second one, and a and a big one, is that there are 8 billion people on the planet who have already who are paying all the bills and and would love to benefit from this as well, and they are past the point where this would be applicable. This would only be applicable in germline. So I think those two things are real showstoppers uh in addition to all the ethical qualms, which are a little bit vaguer as to as to, you know, and and you know, a lot of ethical things change from from uh location to location on their planet and time and age to age. You know, for example, there was near consensus in the United States against interracial marriage and in various other parts of the world, um, and that and these things change. Um so but but in very practical terms, those two things of the you know, the the length of the clinical trial, well, and and the uh inapplicability to most people, all people on the that are currently born. But the the but the answer is we can uh enhance, augment adults, and that’s gonna that’s gonna be more ethical. It’s gonna probably more affordable uh because you can get you can develop something that’s useful for eight billion people rather than a small subset of uh of uh rich babies. And that means that the the cost might be in the in the same range as uh as a vaccine, and we are already enhanced in a certain sense. Vaccines are an enhancement relative to our ancestors, and they’re increasingly being done by something like gene therapy. And I so I think that you know we’ll develop vaccines against cancer in a certain sense, metaphorically, vaccines against a variety of age-related diseases, hopefully all of them.

Eric Verdin:

Well, that’s a fascinating. One that obviously will have to be, again, you know, surrounded by careful ethical consideration, because you could also imagine, you know, is it going to be uh, you know, what happens to neurodivergent individuals? Where do we where do we uh where do we you know lay down the line in terms of what should be improved, what should not be improved, and so on. So it’s going to be an interesting time, you know. Is is uh do you think our are our governments are ready for to tackle all of the ethical questions that will that will be coming with these these possibilities?

George Church:

I would like to believe that uh that that we the people and the governments uh will be ready for it. I think neuro uh atypicals, uh I I would consider myself among those being narcoleptic and you know uh OCD and dyslexic, um they uh should at least be able to have some choice in the matter, right? So in other words, um, you know, for example, I’m not in any rush to cure any of my problems. Uh, you know, if I fall asleep without warning, uh, which makes means I can’t have any job that involves driving or heavy machinery. Um, but you know, uh it you there might be some that if you could some some brain dysfunction you can’t solve uh because it’s your brain is so messed up by you know, say microcephaly or something like that by the time you’re born. But many of them you might be able to dial them up and down. And so you know you could go you could have a phase where you’re incredibly focused on something and you’re you’re actually not very uh capable of social interactions, and then you dial it back and you’re in the you’re the opposite. And uh so I think that that’s one way you can thread this needle a little bit, but uh and I agree with you, it has to be very carefully done. And it goes beyond just safety and efficacy. You know, how do we make sure that it’s not addictive? Uh that it’s not um, you know, some way that you could abuse it where you could, you know, slip it into somebody’s drink. You know, so we have plenty of neuroactive compounds that are abused, both by the individual and by other individuals uh inflicting them. So and governments are not entirely uh innocent as well. Uh making super soldiers would be something that we would have to be very cognizant of. It’s even possible there’d be just like there’s a race to uh a race to make uh uh AGI, artificial general intelligence, there may be a race to make um, you know, natural general intelligence, that is to say, enhancing uh humans. And we d and those races are not they’re not races against, you know, where we’re trying to race against some infectious agent. We’re just racing for the sake of racing, and I think that’s very dangerous.

Eric Verdin:

No, I agree. Thank you. A fascinating way to look at the world. In some way, you know, when you when when people ask, you know, about somebody’s questions, I tell them, you know, look at the fraction of the population that’s drinking caffeine. Um, you know, and it is a is a neuromodulator, a very powerful one that uh, you know, many of us use with great success. So I think there’s uh there are many other ways that this the same paradigm could be uh implemented. To finish, uh I think you know our audience always likes to hear what people who study aging do for their own aging. Is there something that you can share with with our audience in terms of uh what do you focus on? I mean, we all realize that some amazing treatments might come in the future, and I tell people, you know, do everything you can now for the next 10 to 20 years to stay in as good a shape so that you can benefit from it. So what what is what is it for you?

George Church:

I’m not a big fan of anecdotes. Uh plural of anecdotes is not data. I I am very much a fan of uh uh volunteering for clinical trials. Uh uh and I’ve I’ve been a guinea pig most of my life in one way or another. IR IRB approved studies, meaning you know, human subjects, research is proper ethics. I discourage people from doing things that haven’t been tested. And if they are going to do something that hasn’t been tested, it should be in the context of one of these clinical trials, especially they have to be a control group. Now, nobody wants to be in the control group, and I think one of the answers to that is what’s called a crossover trial, where uh you know you blind, you you either have the the drug or the placebo or the or something like a placebo that’s a like a previously approved drug, and then halfway through the the ones that were on the placebo become the experiment and vice versa, and and the patients or the sub-research subjects don’t know which it is. And so that means that every everybody at some point or another is not in the placebo group, which is where they want to be. And I think that’s the the point is that we need uh we will need lots of volunteers uh um to get a lot of these things tested.

Eric Verdin:

I’ve argued that you know our field will will be defined by the rigor and the method that it uses. And and you know, the even though the FDA is quite often criticized for sort of being in the way of the aging field, I think the FDA has been there to protect us and has actually has led us to where we are today. And I think we should recognize this. So I love the idea that uh you embrace this idea of rigorous clinical trials to demonstrate the safety and the efficacy of what we’re going to be doing in the future. So on this, I I want to thank you for uh sharing your insight with us and uh look forward to seeing you in the future.

George Church:

Thank you. Been a pleasure talking to you.

Eric Verdin:

Likewise, thank you.

Brianna Stubbs:

Thank you so much for listening. Please subscribe, share, and give us a five-star review on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Eric Verdin:

We’re not getting any younger yet. It’s produced by Vital Mind Media. The Buck Institute’s very own Robin Snyder is the executive producer. Wellington Bowler is right next to us here directing the recordings. And the esteemed Sharif Azab reached the show together for you.

Brianna Stubbs:

If you’re listening to this podcast, you know that there has never been a more exciting time in research on aging. Discoveries in the labs are moving into the clinic to help us all live better longer. The Buck Institute depends on the support of people like you to carry on our breakthrough research. Please visit us at BuckInstitute.org to learn more and to donate. This episode was sponsored by Ashton Thomas Private Wealth, where discipline shapes vision and vision builds legacy. Learn more at AshtonThomasPW.com.

Speaker:

Investment advisory services are provided by Ashton Thomas Private Wealth LLC and Ashton Thomas Securities LLC, SEC registered investment advisors. Securities are offered through Ashton Thomas Securities LLC, a registered broker dealer and member of Finros CIPIC.