by Buck Institute

April 17, 2024 . BLOG

Meet your hypothalamus. It probably has a lot to do with how you age.

Small and mighty are two words used to describe the hypothalamus, an almond-sized structure that sits deep in the brain, located directly above the brain stem between the thalamus and the pituitary gland.

Similar to the “smart” gizmos that control our home environment (temperature, lighting, security and even turning on the coffee maker at dawn), the hypothalamus helps keep our body in balance by directly influencing the autonomic nervous system to manage our heart rate, blood pressure and body temperature. It also manages hormones that impact other bodily functions like sleep, mood, hunger, thirst, and sex drive, as well as muscle and bone growth.

With aging, the hypothalamus becomes less sensitive to the wide array of neuronal signals that it coordinates in order to keep our systems in balance. Sleep problems? Blood pressure going up? Muscle mass going down? Gaining weight for no apparent reason? A dysfunctional hypothalamus may be playing a role in many of the unpleasant side effects of aging.

The Buck’s Webb lab is taking on the hypothalamus as part of its effort to understand brain aging overall. “This is the newest focus area in the lab and it’s always fun to do new things,” says associate professor Ashley Webb. “I’m fortunate because people in my lab are really into it.”

The Buck’s Webb lab is taking on the hypothalamus as part of its effort to understand brain aging overall. “This is the newest focus area in the lab and it’s always fun to do new things,” says associate professor Ashley Webb. “I’m fortunate because people in my lab are really into it.”

Webb credits postdoc Kaitlyn Hajdarovic with spearheading the project. Hajdarovic first encountered the hypothalamus when she was a lab technician working on circadian rhythms at Rockefeller University. Hajdarovic thinks we are in a new golden age when it comes to studying the hypothalamus, thanks in large part to new single-cell sequencing technology. She describes the arrangement of cells in hypothalamic tissue as uniquely complex, making it perfect for single cell inquiry. “It has so many different types of neurons that produce so many neuropeptides,” she says. “They all signal to each other, and the neurons respond differently to different cues. Looking at individual cells is the only way to get at what’s happening biologically.”

Webb credits postdoc Kaitlyn Hajdarovic with spearheading the project. Hajdarovic first encountered the hypothalamus when she was a lab technician working on circadian rhythms at Rockefeller University. Hajdarovic thinks we are in a new golden age when it comes to studying the hypothalamus, thanks in large part to new single-cell sequencing technology. She describes the arrangement of cells in hypothalamic tissue as uniquely complex, making it perfect for single cell inquiry. “It has so many different types of neurons that produce so many neuropeptides,” she says. “They all signal to each other, and the neurons respond differently to different cues. Looking at individual cells is the only way to get at what’s happening biologically.”

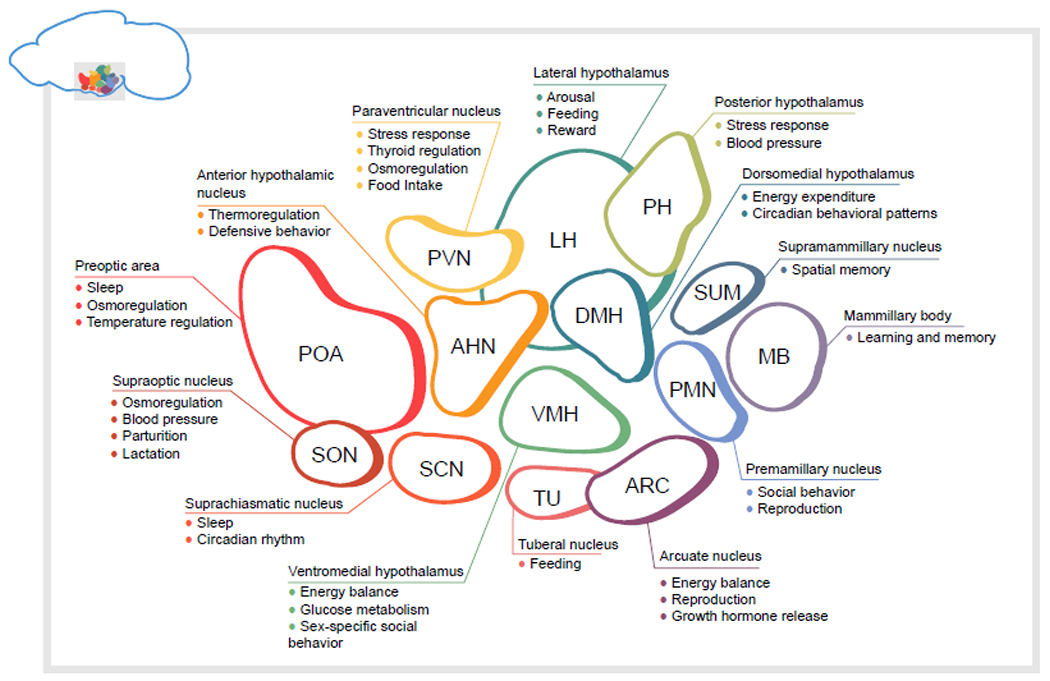

A schematic of the hypothalamus: There’s a lot that goes on in the almond-sized structure that lies deep in our brain!

Webb says looking at the hypothalamus in the context of aging is relatively new. “One of the reasons why people haven’t really looked at aging is because all of these different functions that are regulated by all of these different types of neurons in these little sub-areas of the hypothalamus are studied in individual labs. They really specialize. The research just hasn’t come together in a way that we felt it needed to in order for us to understand this area of the brain and what that actually means for healthy aging.” (If you want to take a deep dive into the hypothalamus, read this journal article authored by Webb, Hajdarovic and grad student Doudou Yu.)

Hajdarovic is working in cell culture, growing human hypothalamic neurons in a dish. Here’s some of what goes on in her head when she comes to work: “What factors go into making a hypothalamic neuron? If we can model changes with age, can we screen for drugs that impact the process? Can we take a hypothalamic neuron that looks aged and make it young again? We’re in the early stages of the work, but I am excited about the questions we want to ask.”

As the first order of business, Hajdarovic is growing POMC neurons which are located in a special area of the hypothalamus called the arcuate nucleus; they help control appetite and glucose homeostasis. When these neurons are stimulated in mice they eat less food. Conversely, decreased activity in POMC cells is associated with increased food intake and obesity. “There’s a possibility that these neurons may be related to age-related weight gain,” she says.

The Webb lab is also studying the hypothalamus in mice, some of it in collaboration with the Kapahi lab. The work involves female animals, because gender differences are significant when it comes to the hypothalamus. The two labs are teaming up to compare data from mice that have had their ovaries removed (generated in the Kapahi lab) and mice that are aging (in the Webb lab) in order to understand the signaling that goes on between the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. The hope is that it will shed light on what happens in human females during menopause.

SHARE